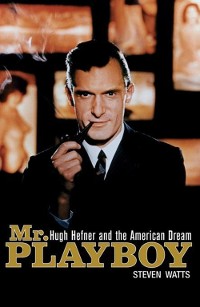

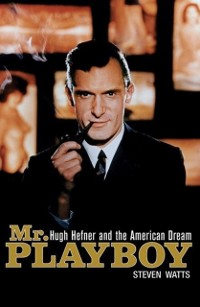

Mr. Playboy

Hugh Hefner and the American Dream

Steven Watts

EPUB

ca. 16,99 €

Sachbuch / Biographien, Autobiographien

Beschreibung

Rezensionen

and expansion, as the famed Playboy Clubs helped him build a business empire that reflected his sybaritic lifestyle in his notorious mansion. Circulation peaked in the swinging '70s (as did an ugly drug controversy); the '80s were less kind, as the brand seemed dated. Hefner resembles a chameleon in Watt's mostly sympathetic portrait, variously appearing as a prescient social critic, an early supporter of civil rights, a generous Gatsby figure and a cranky, obsessive sex addict. The author captures the transitions in American society, though he's repetitive in details and themes, and rather tame, if tasteful, in depicting the sexual exploits that always surrounded Hefner and his empire.<br>Probably the last word on the man behind a million adolescent fantasies. (<i>Kirkus Reviews</i>, July 10, 2008)</p>

Just past the round rotating bed, beyond the hot-tub grotto but before the pajama-draped walk-in, lies … what? If we’re to believe this book, it’s the Truth about Hugh Hefner—and, by proxy, about American life since the 1950s. Of course, the larger legacy of Playboy has been considered long and well (in these pages a couple of years ago, and elsewhere). But Watts, a history professor prone to interpreting American Dreamers (he has written stellar works on Henry Ford and Walt Disney), is wise to draw a narrow bead on Hef qua Hef, dividing his life into tidy quadrants of postwar influence and iconography: as sexual liberator, avatar of consumerism, pop-culture purveyor, lightning rod for feminist ire. He also succeeds in identifying and exploring raging personal paradoxes—hedonist and workaholic, libertine and romantic, provocateur and traditionalist—while resisting the urge to attempt reconciliation. The Horatio-Alger-with-a-libido case he makes—where else but in <st1:country-region w:st="on"> <st1:place w:st="on"> America </st1:place> </st1:country-region> could a repressed midwestern boy rise, and fall into so many sacks, while creating and brand-managing a multimedia empire?—is only intermittently convincing. Still, there’s plenty to enjoy here, from the factual wealth (Watts was granted access to the vast Playboy vaults and draws heavily on his subject’s compulsively kept scrapbook collection) to the photographs aplenty (some offer revelatory glimpses; others give off the whiff of stale cheesecake) to the fundamental pleasures of watching a larger-than-life figure scuttle social norms and satisfy his own lavish urges. ( <i>The Atlantic</i>, March 2009) <p>"Riveting... Watts packs in plenty of gasp-inducing passages." (<i>Newark Star Ledger</i>)</p> <p>"Like it or not, Hugh Hefner has affected all of us, so I treasured learning about how and why in the sober biography." (<i>Chicago Sun Times</i>)</p> <p>"This is a fun book. How could it not be? Watts aims to give a full account of the man, his magazine and their place in social history. <i>Playboy</i> is no longer the cultural force it used to be, but it made a stamp on society." (<i>Associated Press</i>)</p> <p>"In Steven Watts' exhaustive, illuminating biography <i>Mr. Playboy</i>, Hefner's ideal for living -- marked by his allegiances to Tarzan, Freud, Pepsi-Cola and jazz -- proves to be a kind of gloss on the Protestant work ethic." (<i>Los Angeles Times</i>)</p> <p>When Hugh Hefner quit his job at <i>Esquire</i> to start a magazine called <i>Playboy</i>, he didn't just want to make money. He wanted to make dreams come true. The first issue of <i>Playboy</i> had a Sherlock Holmes story by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, an article on the Dorsey brothers, and a feature on desk design for the modern office, called "Gentlemen, Be Seated." Hefner wrote much of the copy himself and drew all the cartoons. But the most memorable part by far was the set of pictures he bought from a local calendar printer of a scantily clad Marilyn Monroe.<br>In this wise and penetrating biography, intellectual historian Steven Watts looks at what Hugh Hefner went onto become, and how he took America with him. Hefner became one of the most hated and envied celebrities in America, dating a long list of his magazine's beauties and always standing just barely on the wrong side of decency and moral uprightness. He also, at one time, had 7 million subscribers to his magazine. Though in time he would lose readers to more explicit magazines on one side and "lad" magazines on the other, the Playboy brand never lost its luster.</p> <p>"...highly-readable and thought-provoking biography written by academic historian, Stephen Watts" (<i>Desire</i>, November 2008)</p> <p>Hugh Hefner started <i>Playboy</i> magazine in 1953 using purchased photos of Marilyn Monroe, and including the article "Miss Gold Digger 1953" about women who "manipulate the legal system for alimony." Hefner positioned the magazine as respectable, with articles by celebrated writers, interviews, and advice columns, accompanied with photos of nude models and ads, all combined to help promote a notion of "the good life." And so it was in his publicly lead private life, complete with famous people, naked women (he was allowed to date other people, his girlfriends were not), and a home in the "Playboy mansion." Watts outlines the man and magazine's influence on the country's notions of personal liberation, sexual freedom, and material abundance. Clocking in at over 500 pages, this is not a gossip book but a well-documented biography written with access to Hefner's over 1800 scrapbooks, the company archives, and interviews. Watts finds Hefner comparable to the subjects of his other books about Henry Ford and Walt Disney in that all were major contributors to aspects of the American dream. Recommended for public libraries and cultural studies collections.<br><b>—Lani Smith, Ohlone Coll. Lib., Neward, CA</b> (<i>Library Journal</i>, September 1, 2008)</p> <p>As he did in his previous books on Henry Ford (<i>The People's Tycoon</i>) and Walt Disney (<i>The Magic Kingdom</i>), Watts carefully details the life of Hugh Hefner and the influence his <i>Playboy</i> magazine has had on American culture. Using unrestricted access to the magazine's archives, Watts skillfully charts the intersection of Hefner's professional and personal history: the “sexual titillation” of his first issue; his mid- to late-1960s championing of leftist politics and writers such as Norman Mailer and Kurt Vonnegut; his 1970s retrenchment after assaults by the women's liberation movement; his financial and personal troubles in the '80s and '90s; and his current position as the “retro cool” figurehead of an institution that is now a “midsize communications and entertainment company.” Watts evokes a time when <i>Playboy</i> was seen by its critics as a key “symptom of decadence in American life,” and is at his best when exploring his subject's early years, showing how Hefner's sexual and material “ethic of self-fulfillment” drove him to challenge “the social conventions of postwar America.” <i>(Oct.)</i> (<i>Publishers Weekly</i>, July 28, 2008)</p> <p>Detailed assessment of the debatably enviable life of America's bachelor.<br>Examining Playboy archives (Hef is something of a pack rat) and Hefner's own journals, Watts (History/Univ. of Missouri; The People's Tycoon: Henry Ford and the American Century, 2005, etc.) constructs a nuanced portrait of Hefner's life that also serves as a panorama of hip culture from the 1950s onward—Sinatra, JFK and many others put in appearances. Watts convincingly argues that Hefner anticipated a number of distinct trends that transformed American society, including postwar consumerism, feminism (whose adherents, generally speaking, castigated Hef) and, of course, the'60s sexual revolution. Watts unearths the narrative of Hefner's childhood in Chicago in the '30s. Within his deeply religious family, he was doted on by his mother and neglected by a mostly absent father, creating "a child who was extraordinarily self-absorbed." Certainly, Hefner was fascinated by sexuality and how its acknowledgement was forbidden, but as he noted later, "Pop culture was my other parent." As an unhappy young man with fond memories of his high-school popularity, Hefner synthesized these personal interests into the legendary 1953 "homemade" first issue of Playboy. (An early nude picture of Marilyn Monroe demonstrated his acumen.) Hefner described the magazine as "a pleasure-primer styled to the masculine taste," and it took off. By the '60s, Hefner was engaged in controversy, via his "Playboy Philosophy,"

Just past the round rotating bed, beyond the hot-tub grotto but before the pajama-draped walk-in, lies … what? If we’re to believe this book, it’s the Truth about Hugh Hefner—and, by proxy, about American life since the 1950s. Of course, the larger legacy of Playboy has been considered long and well (in these pages a couple of years ago, and elsewhere). But Watts, a history professor prone to interpreting American Dreamers (he has written stellar works on Henry Ford and Walt Disney), is wise to draw a narrow bead on Hef qua Hef, dividing his life into tidy quadrants of postwar influence and iconography: as sexual liberator, avatar of consumerism, pop-culture purveyor, lightning rod for feminist ire. He also succeeds in identifying and exploring raging personal paradoxes—hedonist and workaholic, libertine and romantic, provocateur and traditionalist—while resisting the urge to attempt reconciliation. The Horatio-Alger-with-a-libido case he makes—where else but in <st1:country-region w:st="on"> <st1:place w:st="on"> America </st1:place> </st1:country-region> could a repressed midwestern boy rise, and fall into so many sacks, while creating and brand-managing a multimedia empire?—is only intermittently convincing. Still, there’s plenty to enjoy here, from the factual wealth (Watts was granted access to the vast Playboy vaults and draws heavily on his subject’s compulsively kept scrapbook collection) to the photographs aplenty (some offer revelatory glimpses; others give off the whiff of stale cheesecake) to the fundamental pleasures of watching a larger-than-life figure scuttle social norms and satisfy his own lavish urges. ( <i>The Atlantic</i>, March 2009) <p>"Riveting... Watts packs in plenty of gasp-inducing passages." (<i>Newark Star Ledger</i>)</p> <p>"Like it or not, Hugh Hefner has affected all of us, so I treasured learning about how and why in the sober biography." (<i>Chicago Sun Times</i>)</p> <p>"This is a fun book. How could it not be? Watts aims to give a full account of the man, his magazine and their place in social history. <i>Playboy</i> is no longer the cultural force it used to be, but it made a stamp on society." (<i>Associated Press</i>)</p> <p>"In Steven Watts' exhaustive, illuminating biography <i>Mr. Playboy</i>, Hefner's ideal for living -- marked by his allegiances to Tarzan, Freud, Pepsi-Cola and jazz -- proves to be a kind of gloss on the Protestant work ethic." (<i>Los Angeles Times</i>)</p> <p>When Hugh Hefner quit his job at <i>Esquire</i> to start a magazine called <i>Playboy</i>, he didn't just want to make money. He wanted to make dreams come true. The first issue of <i>Playboy</i> had a Sherlock Holmes story by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, an article on the Dorsey brothers, and a feature on desk design for the modern office, called "Gentlemen, Be Seated." Hefner wrote much of the copy himself and drew all the cartoons. But the most memorable part by far was the set of pictures he bought from a local calendar printer of a scantily clad Marilyn Monroe.<br>In this wise and penetrating biography, intellectual historian Steven Watts looks at what Hugh Hefner went onto become, and how he took America with him. Hefner became one of the most hated and envied celebrities in America, dating a long list of his magazine's beauties and always standing just barely on the wrong side of decency and moral uprightness. He also, at one time, had 7 million subscribers to his magazine. Though in time he would lose readers to more explicit magazines on one side and "lad" magazines on the other, the Playboy brand never lost its luster.</p> <p>"...highly-readable and thought-provoking biography written by academic historian, Stephen Watts" (<i>Desire</i>, November 2008)</p> <p>Hugh Hefner started <i>Playboy</i> magazine in 1953 using purchased photos of Marilyn Monroe, and including the article "Miss Gold Digger 1953" about women who "manipulate the legal system for alimony." Hefner positioned the magazine as respectable, with articles by celebrated writers, interviews, and advice columns, accompanied with photos of nude models and ads, all combined to help promote a notion of "the good life." And so it was in his publicly lead private life, complete with famous people, naked women (he was allowed to date other people, his girlfriends were not), and a home in the "Playboy mansion." Watts outlines the man and magazine's influence on the country's notions of personal liberation, sexual freedom, and material abundance. Clocking in at over 500 pages, this is not a gossip book but a well-documented biography written with access to Hefner's over 1800 scrapbooks, the company archives, and interviews. Watts finds Hefner comparable to the subjects of his other books about Henry Ford and Walt Disney in that all were major contributors to aspects of the American dream. Recommended for public libraries and cultural studies collections.<br><b>—Lani Smith, Ohlone Coll. Lib., Neward, CA</b> (<i>Library Journal</i>, September 1, 2008)</p> <p>As he did in his previous books on Henry Ford (<i>The People's Tycoon</i>) and Walt Disney (<i>The Magic Kingdom</i>), Watts carefully details the life of Hugh Hefner and the influence his <i>Playboy</i> magazine has had on American culture. Using unrestricted access to the magazine's archives, Watts skillfully charts the intersection of Hefner's professional and personal history: the “sexual titillation” of his first issue; his mid- to late-1960s championing of leftist politics and writers such as Norman Mailer and Kurt Vonnegut; his 1970s retrenchment after assaults by the women's liberation movement; his financial and personal troubles in the '80s and '90s; and his current position as the “retro cool” figurehead of an institution that is now a “midsize communications and entertainment company.” Watts evokes a time when <i>Playboy</i> was seen by its critics as a key “symptom of decadence in American life,” and is at his best when exploring his subject's early years, showing how Hefner's sexual and material “ethic of self-fulfillment” drove him to challenge “the social conventions of postwar America.” <i>(Oct.)</i> (<i>Publishers Weekly</i>, July 28, 2008)</p> <p>Detailed assessment of the debatably enviable life of America's bachelor.<br>Examining Playboy archives (Hef is something of a pack rat) and Hefner's own journals, Watts (History/Univ. of Missouri; The People's Tycoon: Henry Ford and the American Century, 2005, etc.) constructs a nuanced portrait of Hefner's life that also serves as a panorama of hip culture from the 1950s onward—Sinatra, JFK and many others put in appearances. Watts convincingly argues that Hefner anticipated a number of distinct trends that transformed American society, including postwar consumerism, feminism (whose adherents, generally speaking, castigated Hef) and, of course, the'60s sexual revolution. Watts unearths the narrative of Hefner's childhood in Chicago in the '30s. Within his deeply religious family, he was doted on by his mother and neglected by a mostly absent father, creating "a child who was extraordinarily self-absorbed." Certainly, Hefner was fascinated by sexuality and how its acknowledgement was forbidden, but as he noted later, "Pop culture was my other parent." As an unhappy young man with fond memories of his high-school popularity, Hefner synthesized these personal interests into the legendary 1953 "homemade" first issue of Playboy. (An early nude picture of Marilyn Monroe demonstrated his acumen.) Hefner described the magazine as "a pleasure-primer styled to the masculine taste," and it took off. By the '60s, Hefner was engaged in controversy, via his "Playboy Philosophy,"

Weitere Titel von diesem Autor

Weitere Titel in dieser Kategorie

Kundenbewertungen

Schlagwörter

Steven Watts, biographies of business leaders, biography, Playboy, Mr. Playboy, journalist biography, Hugh Hefner, business biography, American celebrities, Esquire, Mr. Playboy: Hugh Hefner and the American Dream, American icons, biographies of journalists